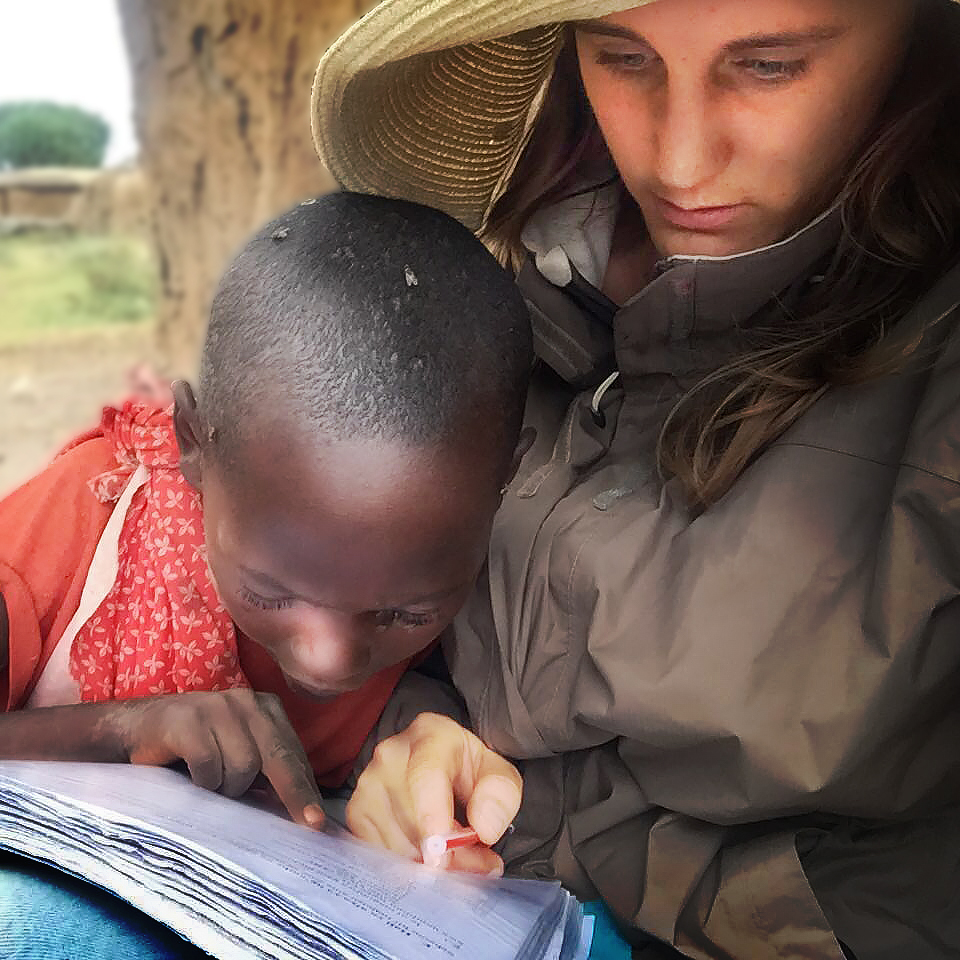

Since sunrise she has been working and playing, unperturbed by the ‘wintery’ chill and rain thirsty earth. Remnants of her previous activity remain dusted on her hands and face. But now she engages completely in reading what appears to be some sort of mundane, educational workbook. Not even the pestering flies landing on her shaved head can disrupt her attention to what I know to be bland, scientific, and altogether child-unfriendly writing. She ever so slightly re-positions herself closer and closer to the paper, leaning across the older lady to absorb every last drop the words have to offer. The pen of the more senior scholar suspends above the paper as the little finger creases the pages, heavy with earnest, flowing with interest, satiated with aptitude. She needs no help.

Behind, evidence of simple, semi-permanent housing emphasizes the rurality of her childhood. Books, electronics, special clothing to fend-off the blistering sun and torrential rains are less common than bare-feet, livestock in the house, and brightly pieced together clothing from the second-hand markets. She is Maasai, a traditionally pastoralist people with ideologies of gendered relations. While a male in her family can expect to grow up to own livestock and land, societal beliefs and attitudes limit her chances for similar achievements. Like many females in rural East Africa, she is destined to leave formal education at a young age. Just because she chose to read an uninteresting survey on livestock disease over playing does not mean that she can translate this desire into an improved future.

Recent movements by pastoralist women to obtain equal rights focuses on overcoming the ideological barriers that have previously limited social mobility. Beyond ideational constructs of gender, though, the social structure in which women reside must additionally be considered to encourage chances for empowerment. The sociologist Peter Blau (1994) once argued social structure influences individual status through two primary components; the existence of opportunities and chances for achieving these opportunities. Women’s pleas for improved access to equal rights must be matched by a social structure evolving to facilitate those demands.

One way to create opportunities for women in a pastoralist community characterized by strong interpersonal networks, is by improving the entirety of the community’s social structure. For example, the multifaceted value of livestock for pastoralists makes investing in the health of livestock advantageous to the enrollment of young girls in school (Marsh et al., 2016). As well, advancements in technology now facilitate integrative learning in even the remotest areas (Petri and Jazbec, 2018). Together, these structural improvements provide young girls with educational opportunities. From here, her actions and achievements recursively impact the community and can spread to empowering other women.

While initially not focused on capturing the structural barriers and opportunities for young women in Tanzania, the picture depicts the potential for change. In the past, this girl would never have been expected to read, let alone understand the complexities of a survey on animal health. But by embracing the demand for inclusive opportunities and recognizing that improving one aspect of the community creates chances for larger structural change, we can imagine a world where this girl achieves the same opportunities for social mobility as the older lady next to her.

Blau (1994). Structural Contexts of Opportunities. University of Chicago Press.

Marsh, Yoder, Deboch, Mcelwain, & Palmer (2016). Livestock vaccinations translate into increased human capital and school attendance by girls. Science Advances, 2 (December), 1–7.

Petri and Jazbec (2018). In Rural Africa, Tablets Revolutionize the Classroom. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/photography/proof/2018/01/africa-technology-samburu-kenya-education/

Commentary on Rachel Tanur's Works: NYC Cow Parade