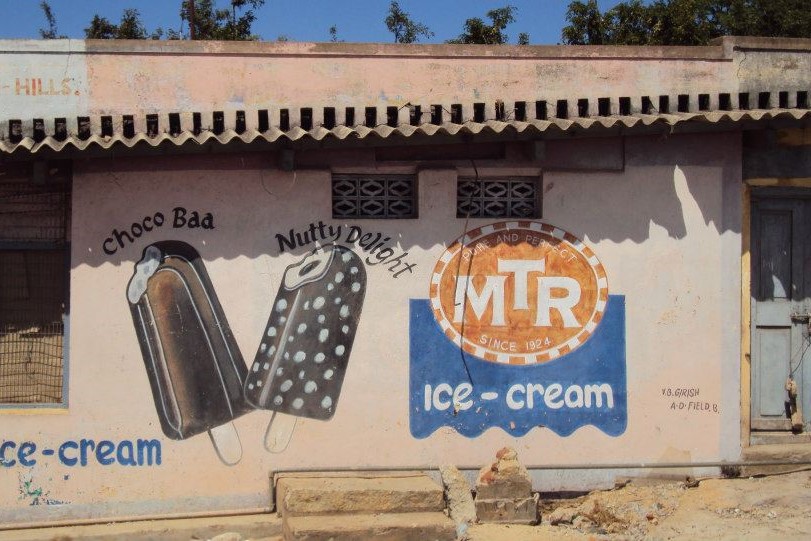

I took this picture of a heavily graffitied wall of an empty house at Nandi Hills, an ancient hill fortress located about sixty miles from the city of Bangalore in Southern India. At first, this image seems like any other abandoned property with a painted wall-advertisement, a common sight one encounters while traveling between rural and urban India. But the hidden comedy spelled out in ‘Choco Baa’, the ice-cream drawings that resemble “hills”, and the peculiar steps that seem to lead nowhere made for a surreal sight at 4800 ft above sea-level. The incongruity of this mural, which was part-graffiti-part commercial, painted an accurate portrait of consumer culture and mass tourism in India today.

Bangalore had become the epicenter of post-modern India since its Information Technology (IT) boom in the new millennium. From a small hill-station and a post-retirement haven, it donned its new identity as techno-polis in a hurry under a decade. Employment opportunities in the IT sector invited interstate migrants increasing Bangalore’s urban population density by 47% in the past ten years1. Paradoxically, illegal commercial establishments in residential areas disrupted “once-calm residential localities”2. As Cohen (1979) suggests, the idea of modern mass tourism primarily serving the recreational or diversionary mode serves as a ‘pressure valve’ for modern man who is alienated by his central surroundings and everyday life (Cohen 1979).

To Bangalore, Nandi Hills was this pressure valve. A once colonial retreat for officials and imperial horticulturists of the British Raj, the Hills had to now accommodate the growing needs of the city’s discontents and the expenses accrued in the upkeep of imperial institutions of a by-gone, but unforgotten era. Mass tourism offered the cure for both. Botanical marvels and majestically aging trees at Nandi Hills were trumped by the marketability of scenic hills, mountains, sunsets, and rolling clouds for disillusioned city-dwellers. To Bangalore city, the Nandi Hills was a ‘back-stage’ or a ‘touristic front stage’ where planned mystification by the tourist organization was necessary to be considered alluring to visitors from the city.

However, the contrived and constructed sceneries and the over-photographed vistas left me wanting for a realization of an authentic experience (MacCannell). As I stumbled across a region away from the scenic “attractions”, I discovered another ‘back-stage’ that was both concealed and yet invited spectators. This was where my touristic consciousness and search for authenticity was realized as striking insight. This wall was a back-stage to a decorated back-stage (or touristic front stage), which conspicuously revealed aspects of the front-stage I’d left below. The socio-economic situation of Nandi Hills, while both connected and disconnected from the ‘front-stage’ at Bangalore, became evident and clear. That walls on a private property about forty miles away lay barren, unclaimed, and freely exploited for the endorsement of branded-goods to those who visit the Hills to get away from the ad-saturated jungle below, struck me as painfully ironic. Economic development in Bangalore had pervaded everyplace around it where its gains and successes had disturbingly displayed itself through the cracks, screaming from this ‘ice-cream wall’. The strip of abandoned houses that lay neglected and unseen behind the touristic space at Nandi Hills was an allegory of Bangalore’s urbanization, as crippling poverty and social instability peeked through all its back regions.

References:

Cohen, Erik 1979 A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences. Sociology 13(2): 179–201.

MacCannell, Dean 1973 Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. American Journal of Sociology 79(3): 589–603.

Endnotes:

(1) http://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/bangalore-population/). (2) https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/sarjapur-road-residents-prote

Commentary on Rachel Tanur's Works: Guatemala Yellow House