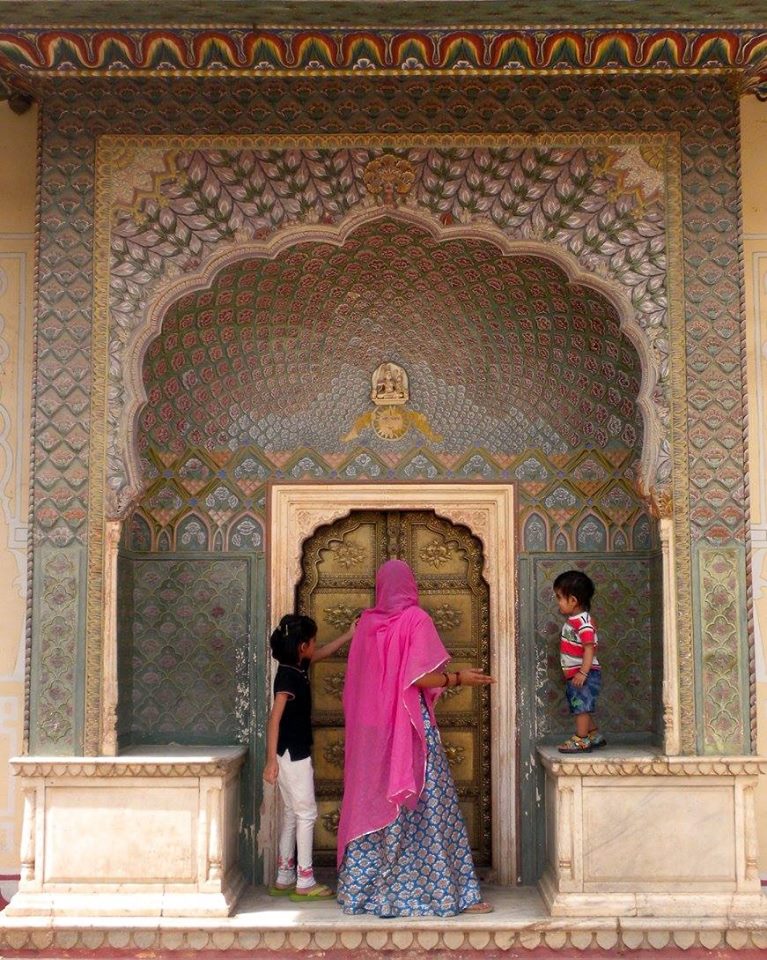

An Indian woman beckons to her toddler as she stands with her daughter in a brilliantly adorned entryway. The woman’s blue and gold sari complements her vivid pink headscarf, stunning yet traditional. She pauses to admire the golden door with her children, a moment of rest on a sweltering, humid day in Jaipur. Her family is on vacation touring the Hawa Mahal, a luxurious royal palace built in the 18th century. This photo captures wealth and abundance, but just outside the palace walls children beg for food. Young mothers hold sick babies, pleading for help. Hawkers sell bottled water, hustling to earn enough money to make it through the day. To enter the tourist destination, one must literally step over people that beg for survival. Images of staggering inequality and poverty saturate depictions of Indian life. This photo counters the story of an impoverished India and speaks to the diversity of Indian narratives. It operates as a reminder to resist the construction of a single narrative of a nation, its cultures, and its inhabitants.

Photography is form of storytelling. It provides a visual representation of sociological phenomenon with the power to make the abstract concrete. In this way, photography is an effective method of communication and explanation. Images convey narratives which operate as a form of cultural discourse and a vehicle of ideology (Polletta et. al 2011). The sociological portrayal of narratives through imagery helps audiences construct meanings about identity, individuality, and collectivity. However, when a single narrative dominates discourse, it silences the diversity and complexity of social experience. Single narratives flatten our conceptions of people and places, ultimately leading to the reification or essentialization of those different from ourselves.

The Sundry Hues of India speaks to the multidimensionality of what it means to be Indian; what it means to be an individual in a nation with 1.3 billion people, 22 official languages, and over 10 major religions. India is a kaleidoscope of cultural heritages, traditions, and lived experiences. By portraying an Indian family as tourists in their own country, this image is a reminder of the vast diversity encompassed within the nation’s borders. The richness of the colors and patterns in this photo are emblematic of this vibrancy of diversity throughout the India. The boy’s crisp denim shorts and striped tee juxtapose his mother’s traditional attire, illustrating that even intergenerational differences in identity exist. The photo implores its audience to rethink their preconceived ideas about India, the East, and the developing world.

This photo also expresses the agency and power of women in Indian society. With her back to the camera, she stands tall. Her intricately woven clothes and wide stance embody her strength and authority. She commands the attention of those around her. An outstretched arm, as it reaches toward her son, symbolizes her critical role as a mother and caretaker of a unified family. Her body is simultaneously oriented toward each of her children- she talks with her daughter and considers the safety of the toddler she encourages to explore. With her head held high and forward facing, the woman’s presence tells a story of female empowerment.

As photographers, we must be cognizant of our positionality behind the camera and the stories our photos may intentionally or unintentionally tell. We take part in narrative construction with each snap of the camera, making it imperative that we critically consider the social, political, or economic ramifications of our visual portrayal of society. Inspired by Rachel Tanur’s ability to depict intimate lived experiences and personal connection in her photographs, The Sundry Hues of India aspires to challenge our assumptions about other people and places.

Polletta, F., Chen, P., Gardner, B., & Motes, A. (2011). The Sociology of Storytelling. Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 109-13

Commentary on Rachel Tanur's Works: Guatamala Veggie Market